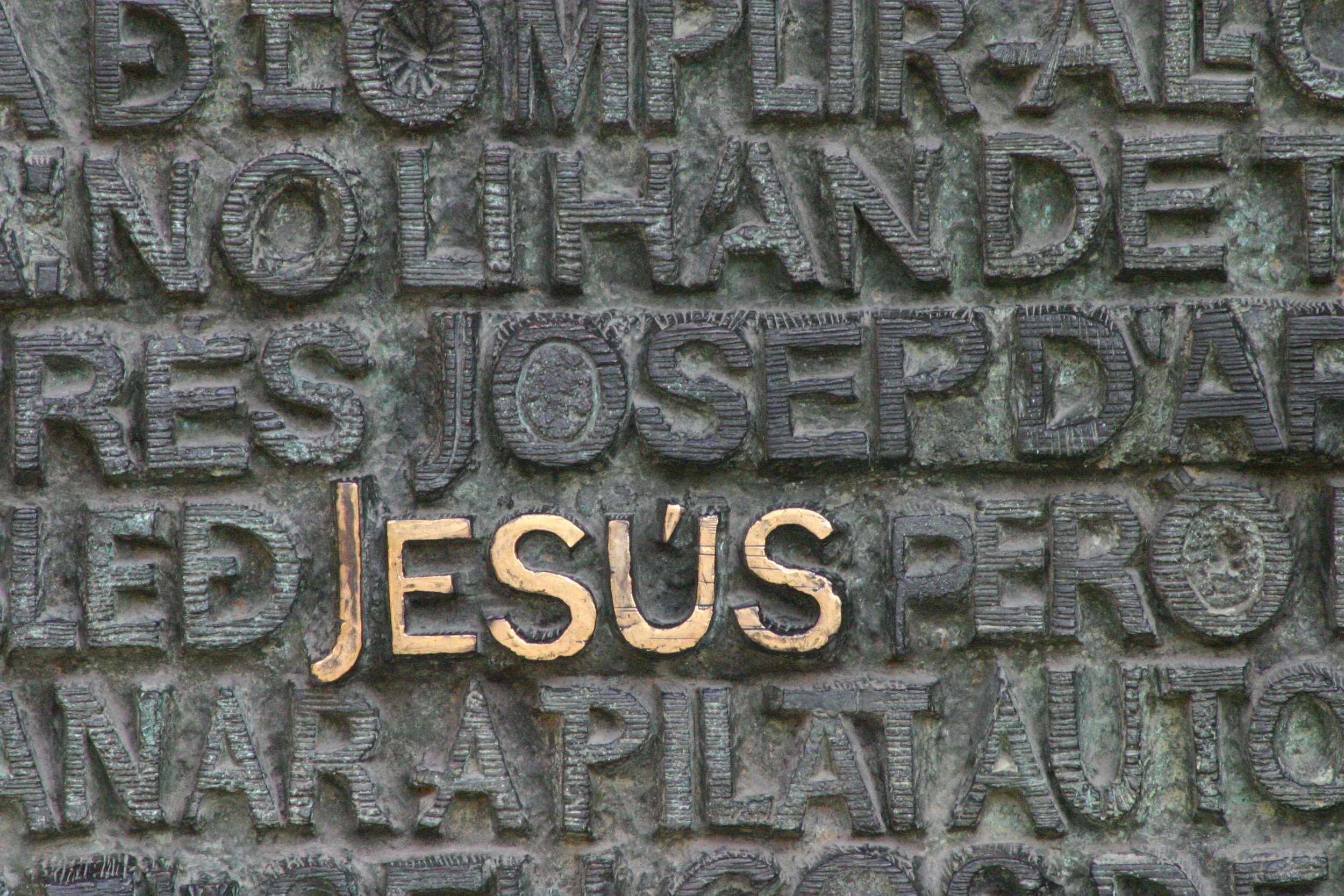

WHAT'S IN A NAME?: MEDITATIONS ON "JESUS MESSIAH"

The Name of Jesus is near and dear to the Christian heart. We do not always profess it as boldly as we should; but Christians nevertheless find joy, assurance, hope, forgiveness and love in this Name. Christians say with Paul, reworking Deuteronomy 30:12-16, “‘The word is near you; it is in your mouth and in your heart’” (Rom. 10:8 NIV).

The word is near us, in our mouth, and erupts into shouts of joy at one moment; then sinks back down into our hearts, into our souls, the next – as we whisper, again and again, the Name of Jesus, like a private liturgy all our own. As Christians we live by this Name, this Word – loving it, cherishing it, holding it close, knowing that this Word holds the power and presence of God. You can read more about the power of this Name here.

But we do not simply sit, repeating rote the Name of “Jesus.” We profess it faithfully, trustingly, gratefully: Jesus Christ, the Christos or Messiah. For Christians believe, they trust in Jesus Messiah. But what exactly does this mean? Does this word “Messiah” make a difference here? Is it a title? Is “Jesus Christ” not a proper name (as some mistakenly think)? To know the answers, we must first look at the meaning of “Messiah” for ancient Israel.

THE AWAITED SAVIOR: THE PROPHET

In his book Jesus: A Very Short Introduction, Richard Bauckham notes that people often placed Jesus into two different roles. The first was that of the prophet. The definite article here denotes a role unlike that of the God’s other messengers. “This prophet was envisaged as a prophet like Moses, who would lead Israel in a new exodus” (Bauckham 86). He was supposed to be a second Moses of sorts – not necessarily a new lawgiver, but a restorer of God’s covenant. This prophet “was expected to come at the climax of Israel’s history to restore the state God intended for them” (Bauckham 86).

Why did they think that Jesus was this great messenger? For one thing, it was thought that the prophet, like Moses, would claim for himself a great authority. Jesus did this – to a controversial degree. For another thing, He was an authoritative miracle-worker. His miracles, some of them like those of Moses, were compared to the works of that great prophet, who was known to perform brilliant “deeds of power.”

For yet another thing, the restorative role fit Jesus quite well. For He had come at a climax of Israel’s own history – and He had come to reestablish and expand covenant relations. He did so in unexpected ways, no doubt; but still He did so, and proclaimed this as His mission.

But He also seemed to reject this title “prophet” as a full description of Him. As Reformed theology notes, He had a “prophetic office” – but He did not want to be seen solely as prophet. For this reason He rejected another title of Moses, that of king, when it was offered to Him. He indeed was king and prophet (and priest as well, as Calvin said); but He could not risk being reduced to any single office, lest people misunderstand Him.

MESSIAH

Messiah was another title accorded to Jesus. This Messiah, purported to be a descendent of King David (as per Nathan’s prophecy in 2 Samuel 7), “was also popularly conceived as a leader who would liberate Israel from the Roman yoke, probably by armed force with divine assistance” (Bauckham 87). Why this was ascribed to Jesus is unclear – most likely it was due to his constant invocation of the coming “kingdom of God,” which He had come to establish. People seem to have seen this claim as Messianic – and they were both wrong and right to do so.

They were wrong in one important sense: Jesus had not come to gain political victories over Roman occupation. He committed no violence and planned no revolution. He did not associate with the zealots, who were the real Jewish revolutionaries of His day. Anyone expecting Jesus to act as a military leader would be disappointed; in fact, they would misunderstand His mission entirely. For this reason, Jesus was rather ambivalent about the title of Messiah: “You say that I am” is his response to the high priest in Luke’s and Matthew’s Gospels (in Mark He gives a straightforward “I am”).

This is not a clear acceptance; but clearly it is not a denial either. It is a roundabout sort of acceptance: I am the Messiah – but not the Messiah you are expecting. Jesus would indeed liberate Israel, but not from political oppression. He would, instead, deliver them from spiritual oppression – from the domination of the forces of darkness in their lives.

This is why, when brought before the high priest of Israel to account for the charges of blasphemy against Him, Jesus did not answer directly. He did not – I repeat, did not – do this to save His own skin. After all, it wasn’t blasphemy to claim that you were the long-awaited Messiah. The blasphemy, instead, came when he spoke of Himself as though He had divine authority. Jesus, after all, did not simply tell people that God had forgiven their sins, as other prophets did; instead, He suggested that He was the one forgiving sins. This sort of act immediately divided the crowds who saw Him: some believed that He was speaking with a special and highly unusual authority; and others (often the more theologically educated) thought that He must be colluding with demons.

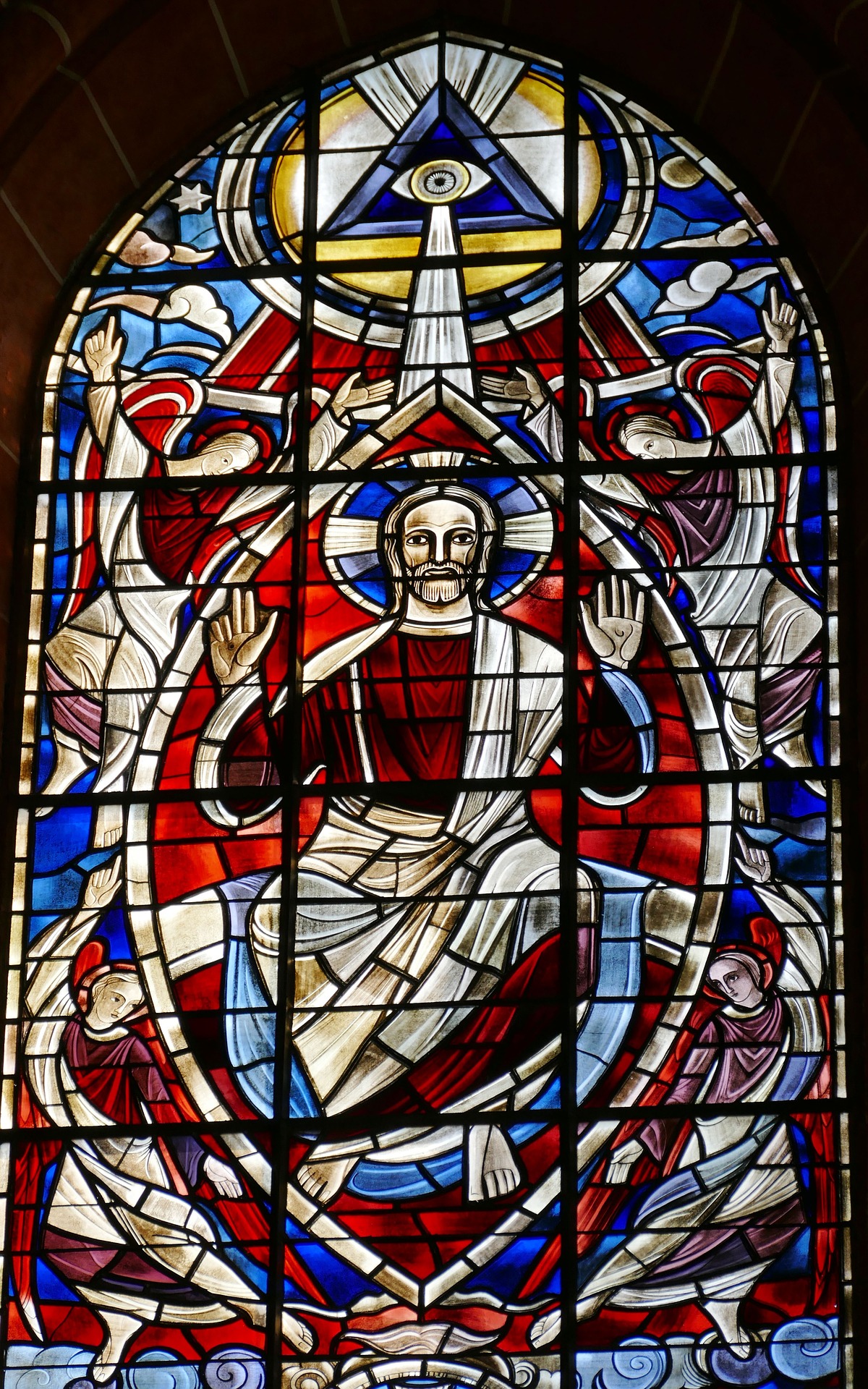

Jesus’ next reply to the high priest, then, would have been foolish as an act of self-protection. Highlighting “another, very different way in which Jesus’ understanding of His Messiahship was distinctive” (Bauckham 89), Jesus said to him: “And you will see the Son of Man sitting at the right hand of the Mighty One and coming on the clouds of heaven” (Mark 14:62, NIV). Drawing from Psalm 110:1 and Daniel 7:13, here “He claims a position of authority, seated on God’s right hand on the heavenly throne of the universe, which identifies him with God’s own sovereignty over the world more closely than the usual image of a human messiah ruling on earth” (Bauckham 89). Elsewhere, Jesus will also identify Himself as the Son of God, the true vine, the one who gives life, etc.

Considering this evidence, displayed in all four Gospels in different ways, Bauckham writes:

Could Jesus act with fully divine authority and exercise the divine prerogative of giving life, while being himself no more than a human servant of God? No, because in Jewish theology such prerogatives belong uniquely to God and cannot simply be delegated to someone else. They help to define who God is. Hence, even in the Synoptic Gospels, Jesus’ claims to divine authority – to forgive sins or to share God’s universal sovereignty – are regarded as blasphemy by Pharisees and chief priests. (Bauckham 93).

Not even including some of Jesus’ more blunt “I am” sayings in the Gospel of John, we nonetheless see Him attributing a blasphemous level of divine authority to Himself – a level that is blasphemous, in any case, if He does not somehow share in God’s own authority. Famous statements from John’s Gospel such as "I am the way and the truth and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me;” or “I am in the Father and the Father is in me” – these only clarify Jesus’ claims even further (John 14:6, 11, NIV). By His own admission, He is to be identified with God, He works with the power of God, and He has the authority of God. In Jewish monotheism, this is a claim to the effect that He is God.[i]

In fact, we see in the earliest Christian documents available, the letters of Paul, a belief that Jesus really did have divine authority, and that the power of God really did manifest itself in and through Him. Paul believed this – and he believed it in terms of Jesus’ Messiahship. This Messiahship, Paul readily knew, was of a different kind; it was not like the militant Messiah who had been expected. Jesus was a spiritual Messiah whose power was manifested in weakness and humility. Paul’s celebration of this is something I will regularly come back to in this blog.

I think that we see in Paul an early and excellent rendition of what it is to have faith in Jesus Messiah. In the next post, I will look at his testimony to faith – an expression of the experience of faith in the Messiah that shows to us the very heart of Christian life!

______________________________________________________________________________________________

[i] Some will, of course, say that these texts should be interpreted in a different way. But most of the justifications for this are highly speculative. One generally has to say that Jesus did not understand what He was saying about Himself, or His followers misunderstood Him, or the authorities did. Or, perhaps, a legend about Jesus developed at a very rapid pace, and had spread throughout the Christian communities (presumably before, or just after, the initial apostles had died). However, it is important to note that there is no concrete evidence for these claims; most alternate hypotheses are highly speculative, have little textual support, display a skeptical attitude to the texts we have from this period, and almost always proceed from a desire to make the early Christian phenomenon compatible with naturalistic presuppositions.

DAN TATE is a writer and blogger at Christ & Cosmos. A former atheist, he’s been surprised and amazed by the God of all things, and he’s passionate about sharing the gospel in ways that respond to contemporary concerns about theology, philosophy, spiritual practice, science, art, and more. A lifelong writer hailing from Upstate New York, he has a B.A. from Allegheny College, an M.A. from Syracuse University, and an M. Div. from Princeton Theological Seminary.